I stood four stories below. We anxiously waited, cameras pointed to the sky as a friend prepared for a jump. He took some time to prepare, a moment of hype, a breath, and began to run.

Regardless of whether or not we agreed with his decision to jump, we stood by to support him. After all, the choice was not our own.

His feet take off the ground as he reaches his hands toward the ledge. He slips. His body lingering four stories in the air as he hurdles toward the opposing wall. What happened? Did he second guess at the moment of execution? Was there some physical error, or was he simply not prepared? His body hit the wall, and we were petrified.

He had explained his backup plan to us, in case something were to go wrong: a bounce back towards the original wall, followed by a near two-story drop to a slanted, metal awning, and then another two-story drop to the ground.

Instinct takes control. He connects, catching the ledge, but barely. A few fingers holding on for dear life. His body fishtails against the concrete giant.

This was the day that I witnessed my good friend, Dylan Baker almost lose his life to the thing that he loved. An experience that would ultimately change my understanding and relationship with fear, both within and outside of movement.

Noah Mittman and I sprinted to the top of the opposing building. Dylan was entirely in shock from the trauma as he yelled, “Fuck! How was my climb up?”

When the brain perceives something as a threat, it activates the stress response: the survival mechanism that humans and other mammals evolved that enables us to react to life-threatening situations.

Acute stress prompts the body and mind to be prepared for emergencies as adrenaline and other hormones are released. In Dylan’s case, he was under immediate threat, and at this stage, many bodily tasks related to long-term function become unimportant. Congratulations, you’ve entered survival mode. Blood sugar levels increase for additional energy for the muscles, cortisol increases to combat pain, additional blood flows to our major muscles for additional strength, and endorphins kick in to make you feel that shit less. You’re basically a Super Saiyan.

It wasn’t until almost two hours later that the severity of the event seemed to really sink in. As we were walking into Whole Foods, Dylan turned to me and said, “I almost died today” in an understanding yet somber tone. I wasn’t entirely sure how to respond. “But you didn’t, and you’re here.” Those were the only words that I was able to muster up. I, too, was just beginning to process what had happened. And that was the only thought present in my mind: How did this happen?

Dylan and I had trained a very similar catpass arm jump just days before. The size in terms of distance was relative. The difference in height was over three stories less than the one that Dylan had slipped between. However, Dylan had executed the smaller of the two flawlessly more than once. I was another story. This jump had been my first experience confronting intense fear within movement. Before my time in Colorado, I had been familiar with fear but not of this magnitude, and my previous encounters had been much more easily worked through. The largest catpass arm jump I had done was about seven feet across and at ground level. This was roughly 12 feet, quite a bit higher, and had a lot more consequence. “Your turn.” Dylan said after his third completion. I stood atop the stadium stairs preparing for some time until I realized something and began to sprint towards the wall in front of me, putting myself into a position where adaptation would be my only option. I jumped, and then I was there, hanging from the other side of the stadium stairs. This was one of my first experiences with the flow state during a stressful and challenging situation. What I had realized was that Dylan spent less time hesitating and more in a position of action. Not just action, but committable action. Why was he spending less time with preparation? Or was he already prepared within the moment?

Emotion influences decision making, and in this case, performance. If you are preparing for a jump and are feeling anxious about the potential outcome, you are more likely to take a safer option. Certain appropriate emotions may be beneficial throughout our training, but fear holds little benefit in terms of performance. Negative emotions hurt performance, both mentally and physically. What starts with fear may lead to anger or frustration, and at that point, your muscles begin to tighten, breathing becomes more difficult, you begin to lose coordination as well as energy. Once you’ve reached the pit of despair, it’s over. You’ll simply no longer have the ability to perform well. Negative emotions also wreak havoc on you mentally, letting you know that you are not confident in your ability to perform the task at hand. Confidence drops, more negative thoughts will join the party, focusing will become difficult, and then your motivation will take a hit. The thing you are doing is no longer enjoyable.

This is where emotional threat vs. emotional challenge comes into play. Emotional threat is generally linked with ego and the idea that failure is unacceptable. Ultimately it leads to poor performance and less enjoyment in the things you are doing. Emotional challenge, on the other hand, is associated with love and enjoyment in what you are doing, regardless if your goals are met. You see each challenge as something to learn and grow from, thus making emotional challenge a highly motivational space, even where high-pressure situations become enjoyable.

I have been meditating since I was young and my most profound takeaway for parkour was mindfulness or the state of being presently aware. The ability to stay consciously aware, both physically and mentally, within a situation negates emotional conflict. In the case of meditation, the goal isn’t necessarily for there to be inner silence but rather to be mindful, striving for internal silence and peace. When a thought, emotion, or some other distraction appears, the idea is to understand and accept the circumstance for what it is and let it pass. Not to say that the thing isn’t important but that now isn’t the time.

There was another jump that Dylan and I looked at together while in Pittsburgh: a 13-foot level arm jump between two rooftops. Once again, he seemed to accept and set aside emotions, the hesitation, completing the jump directly after one small grip test. I did not. I hyped myself up for something that shouldn’t have been as difficult as it was. Instead of jumping, I spent three years being terrified until I was capable of accepting my emotions from that day and setting them aside. And as I had previously expected, the physical nature of the jump had not been very difficult. What was difficult was removing the emotional conflict from the equation.

Why was it that even with an understanding of mindfulness could I not move through fear with a clear and focused mind as Dylan had seemed to? Was I truly moving mindfully?

I started training with the intention of adaptation in mind. Instead of consciously preparing for something, I would take a single breathe and begin to move. This allowed for less thought to occur prior to moving, meaning less emotional interference. This did have its benefits, and I did learn how to react to situations well. However, this didn’t stop fear from creeping in and taking control now and again, and I still had those fearful moments of hesitation.

Our brains, although incredibly complex centers of control, do regularly get in their own way. Our brains don’t necessarily work on precision, but by an assemblage of imprecise processes, though powerful, are prone to fucking up time and again. New neuroscience research suggests how this plays a role in the learning process. The study shows that people who learn the most quickly showed decreasing activity in the frontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex, the parts of the brain that are attributed to thinking and planning. So science is saying: think less, do more. If you are stuck in a situation, instead of trying to think your way through it, try feeling your way through it instead.

I thought back to my challenging moments with Dylan and what I saw in his short preparatory time. He would observe the space, checking distances, surfaces, and his surroundings. It seemed to be quick but thoroughly calculated and executed. He always had an adaptable backup plan that sometimes didn’t seem much like a backup. Followed by a series of simple actions that included wiping his shoes, an action that I never cared for until I noticed it as a signal and not a legitimate action of cleaning. These weren’t some mundane actions but a series of emotionless signals that brought him into a state of mindfulness and allowed space for committable action. The backup plan was indeed that. Not a “bail option” but something that could work as an instinctual response, which explained why some of them seemed ridiculous. They weren’t there to serve as a presently conscious option but truly as a plan for an emergency. All these actions created a chain of conscious changes that led him through the emotional self and into a state of mindful fearlessness, a place for committable action, and ultimately the flow state.

The flow state is a hyper-vivid state of focus where action seems to happen on a subconscious level. Essentially, autopilot. It is the place where an athlete performs at their highest level, both in terms of skill and enjoyment. You’re completely involved, you’re filled with a sense of ecstasy, you know exactly what needs to be done, you lose a sense of self, there is a perceivable lack of time and a sense of self-fulfillment. Have you ever done a jump but don’t recall the process of jumping? You remember your feet taking off, and then suddenly, you were there, with no in-between. The flow state is less of going Super Saiyan and more akin to Korra entering the Avatar State, a place of natural action, reaction, and heightened perception.

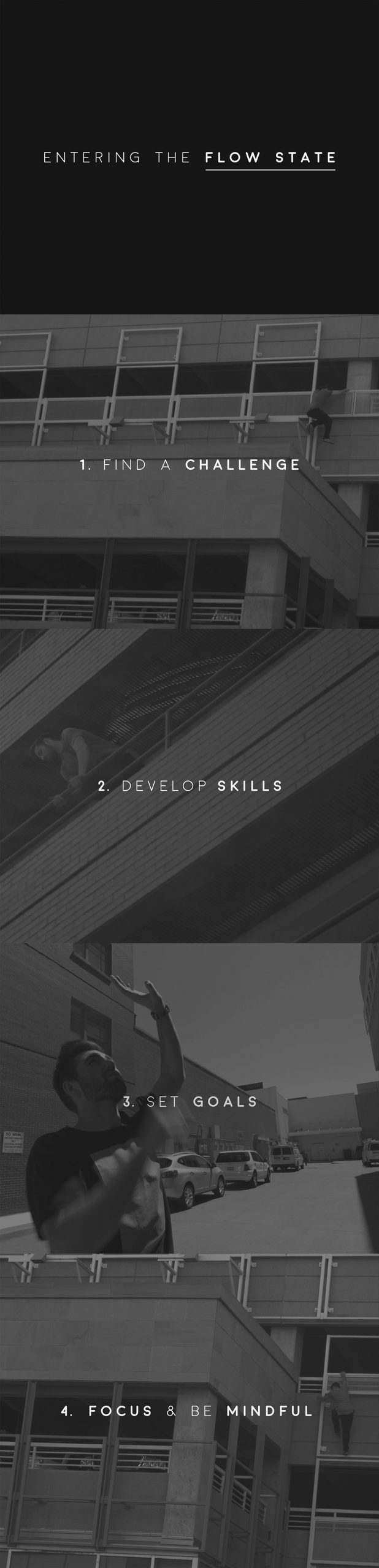

So how does one enter the flow state, and what are the benefits pertaining to moving through fear? The flow state starts with having a high skill level in wherever you are trying to achieve it. In this case, we’re talking about the movements within parkour. This is best achieved through active practice rather than passive learning. Think of active practice as a repetitive physical practice and passive learning as preparation. For many, passive learning becomes a crutch, an excuse for actually not working towards our goals. It’s like being in motion but not taking action. But to be in the flow state, one must not simply be adept in something but put those skills to good use. The flow state happens during challenging moments where your skills and challenge meet or during states of arousal.

The flow state is most easily achieved within challenge. And challenge can exist within anything you enjoy to do, not just movement. If the action is too easy, the mind will stray from the task. However, if the task is too challenging, you’ll just end up being pissed off. Make sure that regardless of the challenge, you have the physical capacity to complete it. If you don’t, spend time developing those skills. Then make sure that you have a clear and concise goal in mind. Let’s put you into Dylan’s shoes for a moment. His goal was to conquer the beast that had almost killed him. He knew he would reach his goal when he made it across to the other building utilizing power and control while maintaining a high level of safety. And finally, be immersed in the task. Eliminate other distractions, giving one-hundred percent of your attention to the challenge. Now, this isn’t the only way of achieving flow. I’ve found myself in the flow state countless amounts of times because of love for the thing I was doing, focusing on the freedom and in the moment details. Once again, mindfulness playing a huge role within the equation.

A year after the fall, Dylan went back, completing the catpass arm jump that almost took his life. This action seemed to lead the direction of his training into the future.

Now I’m not saying this is Dylan’s method for moving through fear to move fearlessly. However, through my time training with Dylan, observing the way he trains, how he interacts within his environment, and relating his actions to how I experienced my own, I was able to piece things together for myself, and in the end, I developed a formula.

OBSERVE SELF

How do you feel? What do you feel? Step one should dictate whether or not you do something. If you are under emotional threat, step away and bring yourself to a better place or save it for another day.

OBSERVE SPACE

Check the space. Make sure all the obstacles are safe, and you know the surfaces. What is happening around you? Are there others training that could get in the way? Is there anything around you that could become a distraction?

CREATE BACKUP

Create a backup plan. Make sure to keep things simple. This should be an emotionless process and one void of negative thoughts: “If something doesn’t go as planned, I’ll push off of the wall and drop to the metal awning.”

ACCEPT AND SET ASIDE

This is the time to accept the reality of things, understand their importance, and set them aside for later. This step may take some exploration of meditation.

MINDFUL PREPARATION

Create a series of emotionless signals to bring you into the present moment. Wipe your shoes, wipe your hands, take a breath. Make sure your full attention is on these actions.

GO!

There should be no hesitation between your preparation and going. Take a breath and immerse yourself fully in the task at hand.

Fear, like any other emotion, should be both understood and respected. By no means am I saying to just pretend to hide your fears in an effort to move fearlessly. To move “fearlessly” takes the utmost dedication to your craft and yourself. You must understand yourself, how you feel, and be mindful of your emotions within the situations you find yourself in.

If you are interested in Dylan’s perspective on fear, watch this interview with him or learn from him yourself at parkourdojo.com