The best journeys in life are those that answer questions you never thought to ask.

Rich Ridgeway

What is play, and why is it important? We all played as kids. No one taught us how, we didn’t need encouragement, it was just an innate desire. I once heard a child say, “Play is what I do when no one’s telling me what to do.” Somewhere along the line though, most of us stopped. Or we moved on to other types of play, more accepted by ‘adults’- things like sports or video games. Adult games often omit one important aspect of the games we played as kids: imagination. The concept of play and games covers a broad spectrum. For the purposes of this article we’re going to focus on where they intersect with creativity.

Imagination is so important for constant growth as a human being. It allows us to ‘see’ beyond what we already know and understand. Movies, airplanes, and the Internet existed only in someone’s imagination before coming to fruition. Do you frequently surprise yourself with your thought patterns or problem solving? If not, I’d encourage you to play more games.

But what exactly is a game? The philosopher Bernard Suits defined the concept of a game in The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia: “To play a game is to engage in activity directed towards bringing about a specific state of affairs, using only means permitted by rules, where the rules prohibit more efficient in favor of less efficient means, and where such rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity.”

What Suits is suggesting here, is that when we’re playing a game we readily accept arbitrary obstacles that are often less than optimal if efficiency is what we’re after. We will generally forsake efficiency in favor of creativity.

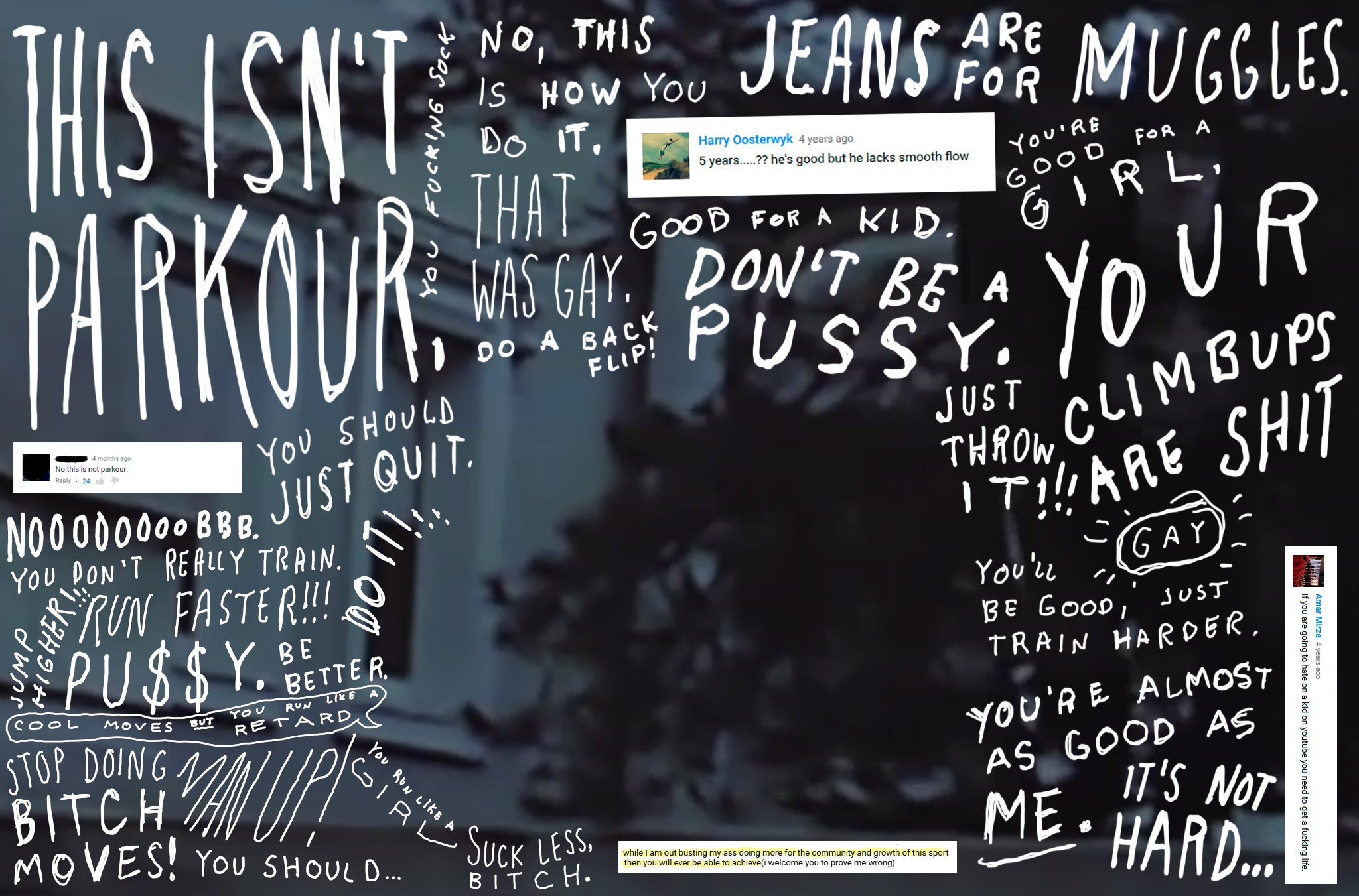

Suits states that “playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” Sound familiar? I don’t know about you, but this is a concise description of my parkour training to date. The ground isn’t lava. The training partner I’m following isn’t the leader. And there definitely isn’t a reward on the other side of the wall. But, these types of imaginative activities encourage or force me to make decisions I wouldn’t otherwise make.

And therein lies one of the fundamental ways we keep our minds developing, supple, and sharp. The slow death of the intellect begins with predictable behaviors and problem-solving. Do you take the exact same way home from school or work every day? Have you ever arrived at your front door and realized you weren’t even conscious of the journey? Why is that? It’s because you’ve already decided on the ‘best’ way to get home. You’ve arrived at an answer, and answers are the death of curiosity.

I think answers are perhaps better thought of as placeholders rather than destinations. Answers can be wonderful if they lead you to a new question or you continue to look for multiple answers to the same question. Maybe consider making your trip home tomorrow into a game. See how many different ways you can get to the same place over the course of a week, no matter how inefficient or impractical. It will begin to shake up some of the rigid thinking you’ve allowed yourself to be compliant with. Getting home is just one example that we can all relate to. I’d encourage you to try to extend that way of thinking to other, more important aspects of your life.

We must first adopt what psychologists call the ‘lusory attitude’ to engage in this kind of behavior. Bernard Suits (who coined the term) defined it as the willingness to accept the arbitrary rules of a game in order to facilitate the resulting experience of play. We acknowledge and accept that the rules don’t really mean anything, and that they’re relevant only during the time we’re playing the game. This willingness to accept seemingly meaningless limitations in order to discover new and creative ways of thinking can be a powerful exercise. Some people may find the limitations confining. The trick though is to view the limitations not as a prison, but as an observatory from which to see the world from a new perspective.

We all engage in a lusory attitude when training, but do we allow that attitude to be metaphorical in other aspects of our lives? Are we getting the maximum benefits from our training? I’m constantly asking myself this question. Training can be like an enigma (a problem generally expressed as metaphorical or allegorical language that requires ingenuity and careful thinking to find it’s solution), and the deeper and more complex our investigations are, the richer the rewards. They’re just waiting for us to find them.

When you go out to train, are you looking for the biggest precision or kong-pre you can find? Do you find yourself focusing on bigger, cleaner, and more powerful technique? While there’s nothing wrong with that, and technique is a vital part of training, technique is objective. Only a few people will ever be truly great, if your criteria are the biggest jump or the furthest kong-pre. But creativity is subjective.

You can be truly great by your own standards, by doing things no one else is doing. Of course, the body has to be fit enough to execute the movements, but it’s all born in the mind. And that mindset gets developed through constant exploration, exploration of personal limits. Almost anything can be a game if you adopt the right mindset. Entering the ‘lusory mindset’ and treating an otherwise unexciting activity as a game can ignite parts of your brain to make new and exciting connections, connections that you wouldn’t otherwise have made. In the process, you’ll surprise yourself, inspire others, and open up a myriad of new possibilities in your training, and your life in general. Don’t be content with being a passive consumer of someone else’s ideas: commit yourself to discovery and innovation.

Photos © Steve Zavitz

Follow Jonny Hart on Instagram.

Want more? Subscribe to help us create more stories like this one and to make sure that we’re able to continue creating the content you love.